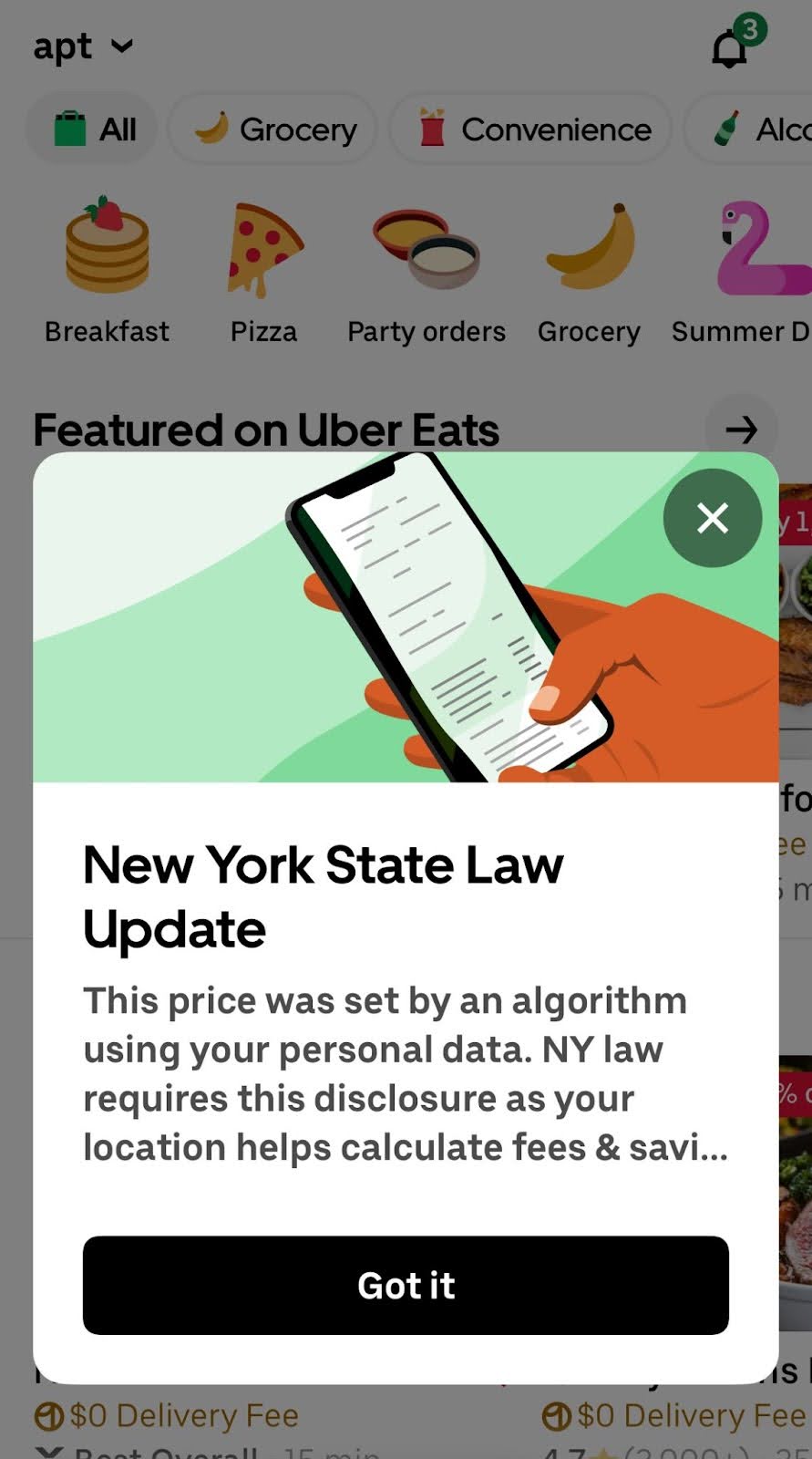

On May 9, New York Governor Kathy Hochul signed the New York Algorithmic Pricing Disclosure Act into law as part of the state budget. Beginning July 8, retailers in New York using any customer information to set prices, from zip code to browsing history, must tag each affected product with a disclaimer conveying the information that “This price was set by an algorithm using your personal data.” In response, the National Retail Federation (NRF) has already sued, asserting the rule is unconstitutional and counterproductive. We agree, as the disclosure requirement compels speech from retailers that is likely to mislead consumers.

Compelled disclaimers can mislead consumers and violate the First Amendment

The Act forces retailers to publicly declare in ominous language that an algorithm was used to set prices using any personal data. Consumers are likely to interpret the disclaimer as an indication that algorithmic pricing is in some way harmful, when the economic literature suggests that algorithmic pricing is likely beneficial for consumers on net so long as the equilibrium quantities sold increase under algorithmic pricing as compared to flat pricing.

Imagine how consumers would interpret analogous mandatory disclaimers:

- “This bagel was produced using Albany tap water. NY law requires this disclosure.” Consumers would understandably start asking questions about Albany tap water safety and quality.

- “This price was set by humans using manual spreadsheet software. NY law requires this disclosure.” Consumers would understandably interpret this as a potential warning about pricing errors or potential overcharging–after all, why else would a disclosure be mandated?

- “This coupon contains a promotion that some consumers are more likely to use than other consumers. NY law requires this disclosure.” Coupons have existed for many decades if not centuries, and the very offering of a coupon in place of an overall price change implies a desire to offer discounts that are more likely to be used by some consumers (e.g., those who take the time to clip coupons) than others. A mandatory disclaimer implies that there is something concerning about this practice, rather than recognizing that lower-income consumers are more likely to take the time to clip coupons, and therefore offering coupons represents a way to offer lower-income consumers lower prices.

Under U.S. law, compelled commercial speech is permissible only when it conveys truthful, factual, and uncontroversial information—and only if it advances a legitimate state interest without being overly burdensome. Here, the compelled disclosure is neither uncontroversial nor strictly factual. For example, retailers using other methods to set prices do not need to display an analogous disclaimer. Instead, singling out algorithmic pricing implies personal data-driven pricing is problematic—even though both economic theory and real-world experience suggest otherwise.

Algorithmic pricing lowers consumer prices for the consumers who need it most

We have previously explored in detail how real-world research shows that consumers and the broader economy tend to benefit from algorithmic pricing so long as the equilibrium quantity increases with the use of algorithmic pricing. Other works reviewing relevant literature have come to similar conclusions.

In their lawsuit, the NRF noted that algorithms enable firms to respond flexibly to supply and demand fluctuations, reducing prices overall. The NRF also notes that many programs—like coupons, loyalty rewards, and cart‑abandonment offers—are merely algorithmic pricing by another name, scaled up.

Stigmatizing these tools through alarming labels risks misinforming consumers, and ultimately discouraging their use. In effect, it turns beneficial promotions into liabilities. More warning labels may translate to fewer deals, hurting consumer welfare. These costs would be disproportionately borne by lower-income consumers, who are the consumers most likely to receive decreased prices from coupons and algorithmic pricing.

Transparency without context breeds confusion

The law’s disclosure requirement sweeps too broadly and lacks nuance. Any use of customer data —even zip code or purchase history—qualifies as triggers. The result: every personalized promo or location‑adjusted sale would have to carry the same stark warning. As NRF aptly notes in its lawsuit, the law is “replete with arbitrary exemptions,” and punishes otherwise benign personalization. For example, online delivery services such as DoorDash and UberEats, which rely on a user’s location to help determine pricing (e.g. for extended delivery to cover longer delivery trips), would be required to display the disclaimer, likely resulting in increased consumer uncertainty on pricing.

Instead of informed consumer choice, the law risks triggering blanket distrust. Shoppers seeing the label next to a price they perceive as favorable may wonder, “What am I not seeing?” Distrust may defeat any transparency goals.

Chilling innovation—and risking economic harm

Finally, the law sets a troubling precedent. If similar algorithmic transparency laws spread, they could hinder investment in legitimate pricing tools and stifle innovation—not just in retail, but across markets powered by continuing innovations in AI. Both innovation and the welfare of consumers are likely to suffer, especially lower-income consumers who generally enjoy the largest benefits from algorithmic personalized pricing.

Conclusion

By framing all algorithmic pricing as inherently suspect, this New York law substitutes fear for facts. It compels speech that misleads, stigmatizes efficiency-boosting technologies, and risks chilling innovation—all without addressing any clear harm. Consumer welfare-enhancing regulation requires evidence-based diagnosis followed by targeted, well-designed remedies, not scaremongering over useful business practices.