Much of the media coverage of the FTC’s lawsuit seeking to block the proposed merger of grocery store operators Kroger and Albertsons has focused on the report that Kroger raised some prices for consumers more than input prices increased for the retailer during the inflationary episode after the COVID-19 pandemic. For many non-economists, this report seemed outrageous. It evoked images of greedy executives “price gouging” at the grocery store, leading to higher bills for consumers and shrinking purchasing power for consumers. But not all inflation is created equal. Among the different types, demand-pull inflation is particularly important to understand, especially when trying to grasp why retailers might increase prices more than the rise in their own costs.

For economists, the report on Kroger was neither surprising nor indicative of anything nefarious. The inflationary episode following the pandemic was mostly demand-pull inflation, the macroeconomic situation that arises when too many dollars are chasing after too few goods and services. In demand-pull inflation, final prices for consumers are expected to rise more than input prices, because consumers are bidding the final prices up.

The Greedflation Narrative Is Back, This Time as “Price Gouging”

The public discourse on “price gouging” has persisted for weeks, and it bears a strong resemblance to the thoroughly debunked “corporate greed”/“greedflation” narrative on inflation that was popular in 2022 and 2023. The same basic pattern is being followed: political commentators observe a macroeconomic phenomenon like post-pandemic demand-pull inflation and attribute it to individual actors rather than broad economic fundamentals.

What is Demand-Pull Inflation?

To understand demand-pull inflation, let’s break it down. Imagine a crowded concert, with only a few tickets left. Suddenly, everyone realizes there are only a handful of tickets remaining. What happens? The value of those last few tickets skyrockets because there are more people wanting them than there are tickets available. This is a simplified way of looking at demand-pull inflation.

Demand-pull inflation occurs when the demand for goods and services outstrips the economy’s ability to produce them. As more people want to buy things, businesses find themselves facing more orders than they can fulfill. As a result, they raise prices.

Demand-pull inflation can be contrasted with cost-push inflation, which occurs when the overall price level in an economy rises due to increases in the cost of production. This type of inflation happens when the costs of key inputs, such as raw materials, labor, or energy, increase, forcing businesses to pass the increased costs to consumers in the form of higher prices for goods and services. While there were supply chain difficulties during the inflationary episode following the COVID pandemic, economists broadly agree that the unprecedented fiscal stimulus response to the pandemic–which succeeded in preventing the pandemic from leading to an extended recession–was oversized in the aggregate. Providing too much stimulus made demand-pull inflation inevitable whether or not cost-push inflation drivers in the supply chain emerged.

Retailers and Price Setting

Now, let’s talk about retailers, e.g., grocery stores, clothing shops, online marketplaces, and various other outlets that sell products directly to consumers. Retailers don’t set prices arbitrarily. Instead, they consider various factors, including input costs (like the cost of raw materials, labor, and transportation), competition, and the demand for their products.

When demand-pull inflation comes into play, it puts retailers in a unique position. The increased demand for products gives them the opportunity to raise prices. But how are they able to raise prices by more than their input costs have increased?

The Mechanics Behind Price Increases

Imagine a retailer who sells handbags. Let’s say the materials and labor costs for producing these bags increase by 5% during an inflationary episode. At the same time, there’s a surge in demand—perhaps due to stimulus payments to consumers and businesses. In this scenario, the retailer is able to sell out of their stock quickly, but customers are also willing to pay more for these coveted items.

Here’s where demand-pull inflation can cause prices to rise more than costs. If the retailer simply increased prices to cover the 5% rise in costs, they would be leaving money on the table. Since customers are eager and willing to spend more, the retailer might decide to increase prices by 10%, 15%, or even 20%. This allows them to maximize profits during a period of high demand.

It makes little sense to attribute this profit-maximizing behavior as “greed” for a number of reasons. Firstly, for-profit firms are always trying to maximize their profits. The “greed” of companies has not changed, merely the macroeconomic circumstances. Secondly, the nature of demand-pull inflation makes attributing blame to individual retailers nonsensical. As this is a macroeconomic phenomenon whereby quantity demanded and quantity supplied begin mismatched–consumers have more money and want to spend it before real production in the economy has time to adjust–a single retailer deciding to only raise prices by the increase in input costs would not prevent additional inflation. Instead, consumers would take their saved money and bid up other prices in the economy.

Supply Chain Challenges and Markups

Another factor driving price increases beyond input costs is the complexity of supply chains. During times of high demand, supply chains can become strained, leading to delays and shortages. Retailers might respond by raising prices to manage this demand or to cover the uncertainty related to when their next shipment of inputs will arrive, or whether the shipment will be at the full expected volume. In other words, when retailers see consumers willing to spend more today and aren’t sure how long their shelves will be empty after the next set of consumer purchases, they may raise prices today to cover the risk of not having a full stock of goods to sell on that shelf tomorrow. After all, the retailers have to pay their bills even if half of their shelves are empty.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities of Demand-Pull Inflation

Demand-pull inflation is a complex phenomenon with real-world implications for both retailers and consumers. While input costs always play a role in determining prices, the relationship between demand and pricing can be more significant. Retailers may raise prices by more than the increase in their costs because of the circumstances presented by high demand, supply chain uncertainty, and the significant time needed for real production to adjust to the rise in demand.

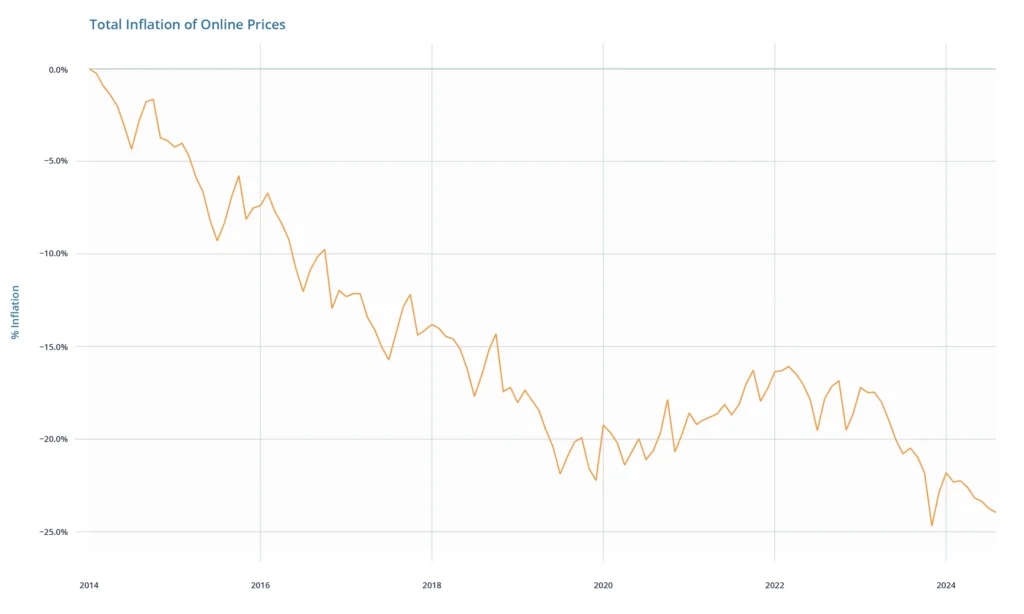

In the broader discourse, demand-pull inflation underscores the importance of recognizing that not all inflation is made equal, and different types of inflation have different consequences. This is particularly important when considering providers of services in the digital economy, whose innovations have helped reduce overall inflation by reducing digital prices by almost 25% since 2014.

There Has Been Digital Deflation Since 2014, Not Inflation

Source: Adobe Digital Price Index data, available for download from https://business.adobe.com/resources/digital-price-index.html

Research has consistently shown that digital prices are actually down since 2014, with work by economists including Goolsbee and Klenow showing how the digital economy has helped to reduce inflation in the broader economy. The work of Goolsbee and Klenow led to the creation of the Adobe Digital Price Index, which can be used to track digital inflation and price trends on an ongoing basis.