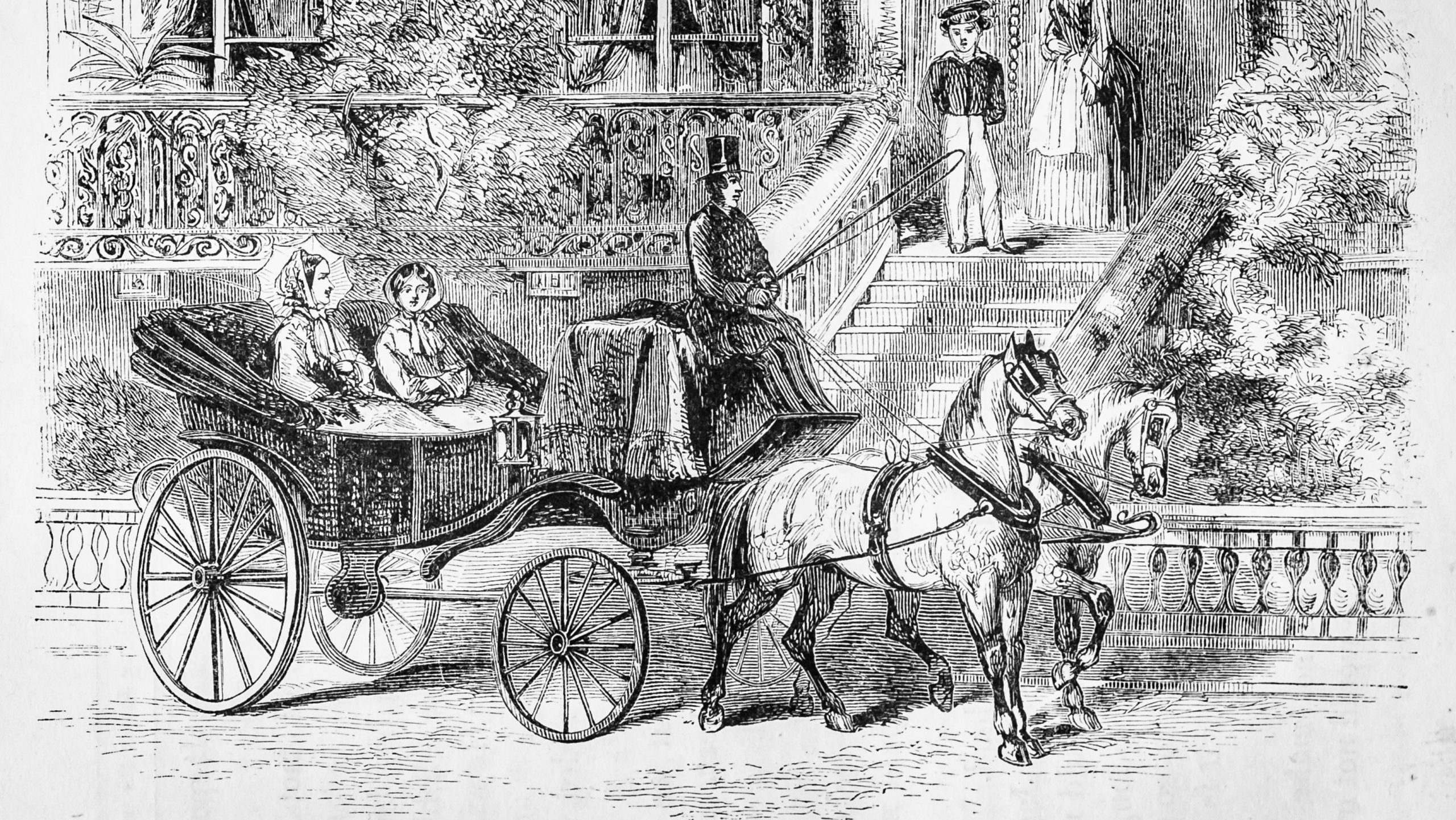

Picture America in 1905. Horse-drawn carriages still clip-clop down Main Street. A few noisy contraptions sputter by, derided as rich men’s toys. Within a generation, the internal combustion engine rewires the economy by adding millions of new professions that never existed during the buggy era: the need for assembly lines and paved roads, construction of suburbs, motels, logistics networks, mass tourism, faster ambulances, and fresher food.

Do we mourn the lost buggy-whip manufacturers? Or do we celebrate the far larger gains in productivity, pay, and consumer well-being that the car era unlocked?

The latter is the right framing for today’s debate over artificial intelligence (AI), necessitating a more holistic look at how the job market will look in an AI-integrated economy. For example, a recent U.S. Senate Health, Education, Labor & Pensions (HELP) Committee minority staff report inaccurately claims that real wages do not rise with productivity and warns that AI could “replace” nearly 100 million jobs. Unfortunately, the HELP committee report does not appreciate the bigger economic picture—just like the early car critics who tallied lost blacksmiths without counting the auto mechanic, the road builder, the freight dispatcher, the motel owner, and the family that could now afford fresh produce year-round. The HELP report focuses on the buggy whip; sound economics focuses on the engine.

Productivity drives compensation higher

The HELP report’s marquee claim that productivity does not drive worker compensation higher relies on a flawed measure. Economists generally use real hourly compensation (wages plus benefits per hour) as the apples-to-apples counterpart to productivity. On that more comprehensive measure, workers’ purchasing power is well above 1973 and correlates strongly with productivity. For example, the BLS/FRED series “Real Hourly Compensation for All Workers, Nonfarm Business” (2017=100) rises from 67.46 in 1973Q1 to 109.21 in 2025Q2, an increase of about 61.9%. In other words, productivity increases have pushed labor compensation higher, and will continue to do so. Workers benefit from productivity-enhancing innovations, as they boost worker compensation.

“97 million jobs replaced” is a horse-and-buggy projection assuming no auto industry

The headline job-loss number in the HELP report relies on a methodology which scores tasks to produce an occupation-level “automation score,” which it interprets as job displacement amounting to around 97 million. That approach equates task exposure with job loss, assumes near-frictionless adoption within a decade, and omits standard general-equilibrium channels, including but not limited to price declines, demand expansion, task creation, and worker flows. Quite literally, the methodology assumes jobs can only go away and never be created.

That is not how the economy works, and it is not how technology diffuses. The car didn’t just “replace” carriage drivers; it reorganized work. We re-bundled tasks, built entirely new industries, and expanded markets because travel got cheaper and faster. AI will do the same for knowledge work: routine tasks get automated, high-value tasks scale, and entirely new complements emerge. That’s the engine effect.

What history and early evidence actually show

When general-purpose technologies develop like steam, electricity, the motor, or software, four things happen:

- Productivity rises. The increased productivity is the motivation for adopting the new technology.

- Unit costs fall and prices follow in competitive markets. Cheaper transport made goods and services more affordable for consumers; AI will do the same for digital and service workflows.

- Employment composition shifts as some tasks shrink and new ones scale. Aggregate employment doesn’t collapse; it reallocates.

- Overall compensation rises as a result of competitive reallocations in a higher-productivity economy.

The best early AI field studies already show double-digit productivity gains in customer support and professional writing, with the biggest boosts for less-experienced workers—exactly the human-capital story you want if you care about inclusive growth. That pattern mirrors the automobile era, where entry-level mechanics and service workers rode a new ladder of opportunity even as blacksmithing waned. It also echoes the introduction of modern industrial robots, where increased robot use “contributed approximately 0.36 percentage points to annual labor productivity growth” while raising total factor productivity, lowering output prices, and not significantly reducing total employment.

Consumers are the big winners

Cars didn’t just create jobs; they slashed the effective price of distance. AI slashes the effective price of cognition—drafting, summarizing, coding, searching, troubleshooting. When the “cognitive miles per gallon” goes up, firms can serve more customers per worker-hour. In competitive markets, those savings show up as lower prices and better service. That’s not just a theory; it’s how every new general purpose technology has worked.

So what should policy do: protect buggy whips or scale engines?

A pro-worker, pro-competition agenda embraces the engine and manages the transition:

- Accelerate diffusion. Help small firms, schools, and public agencies adopt modern AI copilots and workflows. As with rural electrification and the interstate system, the broad gains come when everyone can plug into the new technology.

- Keep markets contestable. Competition policy based on application of the consumer welfare standard should ensure cost savings flow through to workers and consumers: higher pay where skills are scarce and productivity rises, lower prices where firms compete and new efficiencies reduce costs. We see intense competition between firms making large investments in innovation, infrastructure, and service improvements in the AI space today, strongly suggesting a healthy ecosystem for consumer welfare enhancement.

The economic bottom line

America isn’t enriched by freezing the economy in the horse-and-buggy era. Our economic successes are driven by building around innovative technologies—creating new tasks, new revenue streams, and new ways to live. The same logic applies now. When we look at technology honestly, AI is much more of an economic engine than a buggy whip guillotine: it raises productivity, pushes down prices, and, with the right complements, lifts pay for many workers.

We honor the past by helping people through the transition, not by trying to stop the engine. The buggy whip had its moment. The AI opportunity now—like the automobile then—is to make sure every American can take the wheel.