Every technological revolution brings understandable fears about the imminent obsolescence of human workers’ skills. Today, that alarm has spiked with rapid advances in generative artificial intelligence (AI) leading to concerns that human workers themselves may be obsolete. Headlines warn of mass unemployment, while corporate executives announce workforce reductions they attribute to AI capabilities. Yet a careful examination of the empirical evidence paints a considerably more nuanced picture that should inform public discourse.

History offers instructive lessons about the gap between technological predictions and labor market realities. The examples of the automated teller machine (ATM) and AI in radiology are particularly illuminating examples that demonstrate why we should expect neither utopia nor ruin from AI deployment. Instead, we should expect noticeable productivity growth resulting from task switching within and between roles as human workers and AI tools specialize based on comparative advantage.

The ATM Paradox: Labor-Saving Technology Created Jobs

When ATMs were introduced at scale across American bank branches in the 1970s and 1980s, the conventional wisdom held that bank tellers would soon join telephone switchboard operators in the dustbin of economic history. The logic seemed unassailable: machines that dispense cash and accept deposits would inevitably eliminate the humans who performed those same functions.

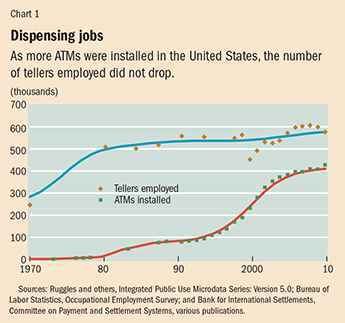

The data told a different story. As economist James Bessen of Boston University documented in his research, the number of bank tellers in the United States actually increased as ATM deployment accelerated. From the 1980s to 2010, while approximately 400,000 ATMs were installed across the country, bank teller employment grew from around 500,000 to nearly 600,000.

This growth in the number of tellers accompanying the deployment of ATMs was possible because the nature of the teller’s job evolved following the deployment of ATMs. With routine cash transactions handled by machines, tellers became increasingly valuable for relationship banking tasks like helping customers with complex needs, selling financial products, and building the personal connections that differentiate one bank from another. Some routine bank teller tasks were automated, but the job was transformed rather than eliminated. When the number of bank tellers finally declined consistently in the 2010s, it was due to a different innovation entirely: mobile banking. Mobile banking reduced the frequency of customer trips to the bank and therefore reduced the demand for relationship banking staff.

The AI Expert Who Cried Wolf at the Radiology Department

Fast forward to 2016, when Geoffrey Hinton, the Turing Award-winning computer scientist often called the “Godfather of AI”, made a prediction that sent shockwaves through the medical community: “People should stop training radiologists now. It’s just completely obvious that within five years deep learning is going to do better than radiologists.”

Coming from one of the most accomplished figures in machine learning, this was not idle speculation. Medical schools and prospective physicians took notice. Some reconsidered career paths. Articles proliferated about the imminent end of radiology as a profession.

Nine years later, we can assess this prediction against reality. The number of radiologists has grown, not collapsed. According to a New York Times interview, at the Mayo Clinic alone, the radiology staff increased from approximately 260 in 2016 to over 400 today, a 55 percent expansion. Nationally, the profession faces not a surplus of displaced workers, but a critical shortage, with imaging backlogs stretching for months at some facilities.

To his credit, Hinton recently acknowledged his error. He admitted he spoke too broadly, focused too narrowly on image analysis, and got the timing wrong. His revised prediction is more modest, anticipating that AI and radiologists will work in combination, with AI making human practitioners more efficient and accurate. This is augmentation of human labor, not replacement of human labor.

What the Evidence Actually Shows

These historical examples provide essential context for interpreting the emerging body of empirical research on AI’s current labor market effects. The findings suggest a pattern more consistent with the ATM story than with catastrophic predictions.

Babina and Fedyk synthesized recent research in a Brookings Institution analysis, finding that contrary to widespread fears, AI adoption at the firm level has been associated with increased employment, not layoffs. Companies that invest in AI tend to grow faster, hire more workers, and innovate more intensively. The aggregate picture shows AI mostly complementing human labor rather than simply substituting for it.

A landmark study by Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, and Lindsey Raymond examined the introduction of a generative AI assistant among over 5,000 customer service agents. They found an average productivity increase of 15 percent, but with a striking pattern: the benefits accrued disproportionately to less experienced and lower-skilled workers, who saw gains exceeding 30 percent. The most experienced workers saw minimal effects. AI appeared to be leveling the playing field by disseminating best practices from top performers to newer employees.

This finding inverts the typical pattern of skill-biased technological change that characterized earlier waves of computerization, where new technologies tended to complement high-skilled workers while substituting for the labor of lower-skilled workers. If AI tools can accelerate the learning curve for less experienced workers, the distributional implications could be genuinely progressive.

Research from MIT Sloan similarly finds that AI’s employment effects depend critically on the breadth of task automation. When AI can perform most tasks within a job, employment in that role declines by approximately 14 percent at the firm level. But when AI automates only some tasks within a role, employment often increases, as workers redirect their efforts toward higher-value activities that AI cannot replicate. The lesson echoes the ATM story, as automation of some tasks and task switching by human workers is different from wholesale replacement of jobs.

Distinguishing Signal from Noise in AI Layoff Announcements

A major driver of recent public discourse around AI and employment is the recent practice of many companies attributing layoffs to AI. Headlines about AI-driven layoffs deserve scrutiny. While some workforce reductions genuinely reflect AI-enabled efficiency gains, AI gains have become a convenient corporate narrative that may obscure other motivations, such as corrections from pandemic-era overhiring, cost pressures, or responding to a cyclical slowdown in the economy. The New York Times noted signs that many recent layoffs attributed to AI were due to non-AI financial motives, a trend it dubbed “AI-washing” layoffs.

Wharton’s Peter Cappelli has observed that when researchers examine companies actually implementing AI, “there’s very little evidence that it cuts jobs anywhere near the level that we’re talking about. In most cases, it doesn’t cut head count at all.” Goldman Sachs economists forecast only modest and temporary employment impacts from AI adoption, and have found “AI’s impact on the labor market remains limited and there is no sign of a significant impact on most labor market outcomes” thus far.

Forrester research even documented cases where companies laid off workers ostensibly for AI reasons, and then subsequently rehired, which suggests that even some layoffs actually attributable to management expectations of AI substitution reflect premature optimism about technological capabilities rather than actual automation. The disconnect between corporate AI narratives and operational reality warrants skepticism at present on attributions of employment decisions to AI.

Informed Optimism Is the Best Path Forward

The weight of current evidence supports cautious optimism about AI’s employment effects. The World Economic Forum projects that AI and related technologies will generate 170 million new jobs by 2030 while displacing 92 million, yielding a net increase of 78 million positions globally. But this aggregate growth outcome will be accompanied by task switching and similar transition challenges, which may not always be frictionless.

History suggests that Hinton’s radiologist prediction and countless ATM-style forecasts share a common analytical error: they conflate the automation of tasks with the elimination of jobs. Jobs are bundles of tasks. When some tasks are automated, other tasks often become more valuable. New tasks emerge, and demand shifts. The economic system adapts in ways that static analysis cannot capture.

None of this guarantees that the future will resemble the past. AI capabilities are advancing rapidly, so in some cases today’s labor augmentation tools may become tomorrow’s labor replacement technologies. But the evidence from the first years of the generative AI era suggests that, so far, AI is making most workers more productive rather than making them obsolete, just like earlier waves of automation increased productivity without rendering human workers obsolete.

The bank tellers didn’t disappear, they turned into relationship bankers. The radiologists are still reading scans, aided by AI tools. And for most workers, AI is proving to be more of a partner than replacement.